Edge of Visibility is a multimedia exhibition featuring works by artists who address contemporary concepts through individual practices and the use of repetition, color, and abstracted imagery. The artists reflect on personal experiences to explore identity and origin. Tension and harmony are made visible through process and material, representing cultural and historical topics, and also a passage of time. The exhibition features work by Alia Ali, Hasan Elahi, Sahar Khoury, and Jordan Nassar.

Artist Statements

-

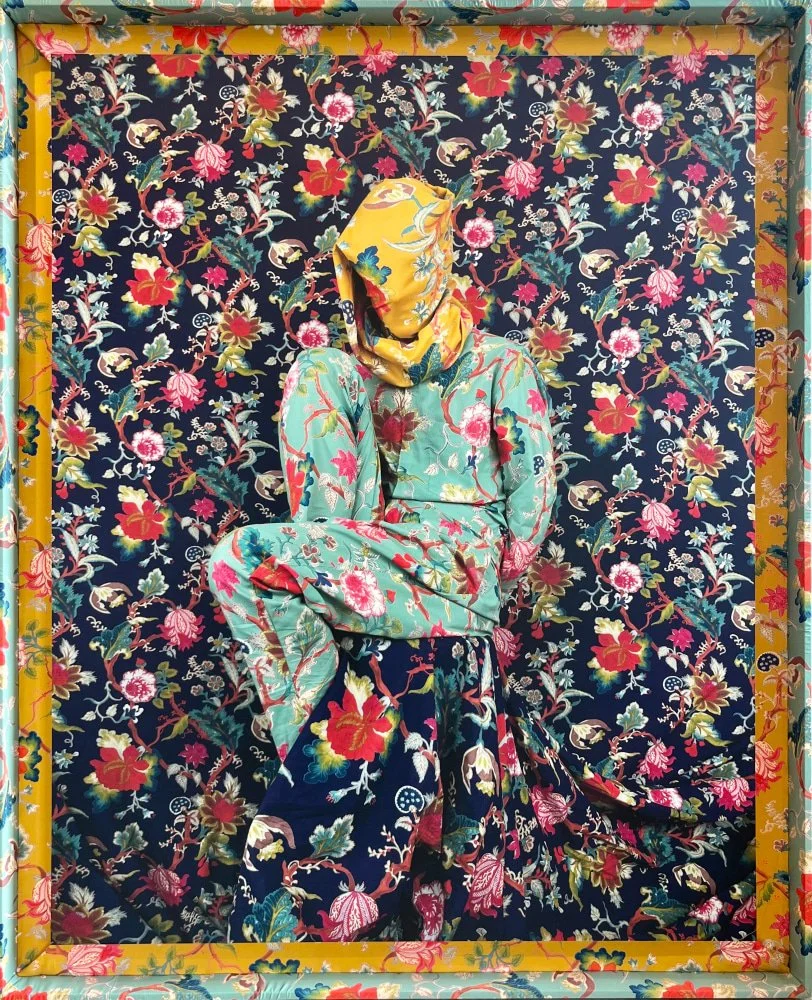

Jade is a spirit, a djinn who lives in Jaipur, if one could say she “lives” anywhere at all.

Jade is an agile shapeshifter, appearing and disappearing, morphing at will through time and space. Supernatural —exponentially natural; extraterrestrial—all possibilities of terrestrial existence all at once; from the outer galaxies to deserts, from the depths of the ocean to our pockets. Djinn live amongst us, but it is entirely their decision if we are to see them or not. They do not control humans; on the contrary, they create circumstances or opportunities, and leave us to make our own choices.

A flash, a shadow, something that sounds like a whisper but is more like the touch of a feather. Pay attention; these are the interstices of possibility. The individual works in JADE—Wink, Blink, Lotus, Clouds, Peak, Pick a pocket, Day dreamers, and In-direct gaze— follow the spirit as s/h/e morphs from one essence to another, inhabiting a stone or a tree, then s/h/e is a serpent, or the last rays of the sun falling on a mountaintop, and s/he is also the sense of warmth left behind when the sun is gone.

Djinn existed long before monotheism, forget the manichean binaries for a moment. There is no hierarchy, there is only pause, a moment of quiet after a glass shatters on the floor, or the scrape of metal on metal. The sudden suspension of jarring sound and sensation is a blessing, a safety, the djinns are cleared from the room. But understand, the djinn is both chaos and calm, for one cannot exist without the other.

It may be the surprising flash of sun on a mirror, something that seems trivial in the mind but not in the soul, where it resonates. And it is a signal that whatever choice you made, it was yours to make. Jade only lays out the possibilities of things before moving on. H/e/r sudden presence sparks the imagination, and H/e/r departure leaves the space to consider

the potential of the idea, and the quiet to hear one’s deepest thoughts.

The story of JADE is a collaboration that brought a team of masters from various points on the globe together to create the final images. The djinn had her hand in things all along, because of course she is everywhere. The weavers and printers in India, they let us apply the wood blocks to the chanderi silk. Lotus, clouds, and blossoms in indigo, green and gold, the color of jade, between earth and sky. The tailors imagined costumes from around the world, western shirt and nehru jacket, lehenga skirt and trousers, turban and gloves. And back to New Orleans where Jade pivoted and flew about the studio, impossible to be captured by any lens– only in fleeting sparks of light in constant motion. Then off to the printers in Paris while embroiders in Jaipur prepared the fabrics, who worked the leaves and flowers of the upholstered frames— blossom, in full bloom and constellation. All the while, framers in New Orleans and Morocco would build the most robust reveal the windows in which we get a glimpse of Jade, the Djinn.

It takes a community to create a spark.

Back and forth, from here to there, all of us up to our ribs in this single project, and all of us attentive to the moment of inspiration that turns work into purpose, an idea into a work. She entered the space(s) and left something behind, and now we will continue to work together as we have learned to do. Our individual and collective imagination is expanding around costume and storytelling, and infinite possibilities. Jade becomes a space in the artist’s practice now and for what is to come.

-

Yemen is and always has been famous for its honey. As newborns, honey was placed below our lips so that the first taste of life was sweet and that we were all united by the sweet taste of our land.

NOOK (2023) evokes the experience of the diaspora. It draws attention to those of us whose existence requires us to carve our own spaces of identity. The only way to do so is to create our individual and unique space(s) of retreat.

The title “Nook” refers to sublime places, havens, and safe corners. Whether this is with ourselves at table- lined passageways where we people watch- meditating on how we fit into all of this, looking out of bus or airplane windows, literally in the clouds, both mentally and physically. Meditations that are themselves aspirational. And then there are the reconstructions—mental and physical—of nostalgia, and dual existence. Remembering and re- remembering memories, how to hold/move on, knowing very well that what we remember is only our last memory of an event. As it slips away, we hold on with objects like photographs (to mark moments), maps (to mark places), and songs (to mark emotion). All this to say that we are entering into existences that are not dual, but multi-layered, all at once.

The series is composed of six images that work together, both linear and cyclical, creating a portrait of a multi-layered existence. The characters—the -cludes—are either included or excluded. What about us? Must we draw our power from one culture or another? Perhaps our only form of existence is to choose seclusion; where our agency is influenced by powers none other than our own.

The portraits work together to create a constellation: Wanderlust, Legend, East, West, Fragment I and Fragment II. Wanderlust depicts a seated figure, childlike, full of hope and anticipation, eager to depart. Legend indicates a sense of direction, as well as the ability to choose. Here is a woman set on a path of motion, moving from right to left, from east to west. Emotion becomes motion: she glides along a path, the angle of her torso confident yet simultaneously pulled by the gravity of departure, her feet leading forward. *

Continuing with the series, a semi-reclining figure in kurta, loose trousers flowing into the frame of yellow that speaks of warm light and ochre sunsets. This is East. Then there is West, perched on a chair, in straight leg trousers and shirt, a pale face, cloth cascading like loose, long blond hair. East and West can stand side by side, or separated by Legend, who orients and re- orients.

Finally, Fragments I & II form a diptych: two halves of the body, echoing the duality of diaspora. Fragment I is the torso, a floral-patterned shirt.

It is only when the viewer sees Fragment II that they perceive the dress as Asian: the kurta is too long to be a shirt, the trousers too full.

These printed fabrics were custom made to resemble a dress worn by my Yemeni grandmother. The clothing was tailored with the idea of fusing together east and west. While I come from two nations that no longer exist (South Yemen and Yugoslavia), I know my blood is Yemeni and Bosnian. My place of birth is Austria, and I hold passports from Yemen and the US. I cannot ignore that I received an education from the British and the US, my colonizers of the past, and my right to citizenship from the Saudis and the US, who have invaded my homeland.

And yet, by holding these two passports, the black (Yemeni) and the blue (US)—both emblazoned with eagles, one opening from the left and one from the right—side by side, I realize that while one gave me everything I came from, the other has given me everything that I have chosen to be. With the blue passport I can travel, be evacuated, speak, and choose. And yet, while my body can choose to be in one place, my mind can be somewhere else, and my soul holds them together.

NOOK confronts the question of citizenship, belonging, and identity to offer a counter-narrative. The empirical associations with citizenship are arbitrary; a power that supposes superiority. Migrants, or multinationals, are often perceived as less than whole, when in fact we are overflowing.

There is not less, there is more than.

*Note: the works Wanderlust, Legend, and East are not in the exhibition.

-

In 2002, Hasan Elahi was wrongly identified as a potential terrorist, leading to a six-month investigation by the FBI. In response, he began a long-term project called Tracking Transience, 2002–present, in which he publicly posts documentation of his daily activities so that the FBI can monitor him more easily. By transforming the normally secret and coercive act of surveillance into a public and voluntary one, the project satirically embraces the erosion of civil rights in America, especially the increased surveillance of immigrants, people of color, and Muslims in the wake of 9/11.

Reform is comprised of 50 photographs from Tracking Transience taken across the United States. The photographs are overlaid with the pattern of colored bars that US television stations use to calibrate their signal. This pattern was also used to test the Emergency Broadcast System across those same television screens. According to Elahi—who moved to Detroit from Washington, DC—the stripes also refer to the abstract paintings of the Washington Color School of the 1960s.

Elahi’s projects dealing with surveillance, privacy, migration, citizenship, and the challenges of borders have been presented at SITE Santa Fe, Centre Georges Pompidou, the Sundance Film Festival, the Gwangju Biennale, and the Venice Biennale. He is currently Professor of Art in the James Pearson Duffy Department of Art, Art History, and Design and Dean of the College of Fine, Performing and Communication Arts at Wayne State University.

-

Khoury pays homage to the iconic Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum (c.1904–1975) by creating a 20-foot-tall clock radio tower. Renowned for her vocal range and impassioned performances, she became a symbol of pan-Arab unity and was known as “Egypt’s Fourth Pyramid” and the “Mother of Arabs” (the word umm is Arabic for mother). For nearly four decades, Egyptian national radiobroadcast Kulthum’s live concerts on the first Thursday of each month, making these events accessible to millions.

To honor this legacy, Khoury and the Wexner Center commissioned an original score titled UMM / AL ATLAL from artists Lara Sarkissian and Esra Canoğulları (aka 8ULENTINA) to play once an hour through the found radio cage construction. The tower is a timekeeper and translator, adorned with lyrics from Kulthum’s “Al Atlal” (The Ruins), a mournful love song that became symbolic of anticolonial resistance.

-

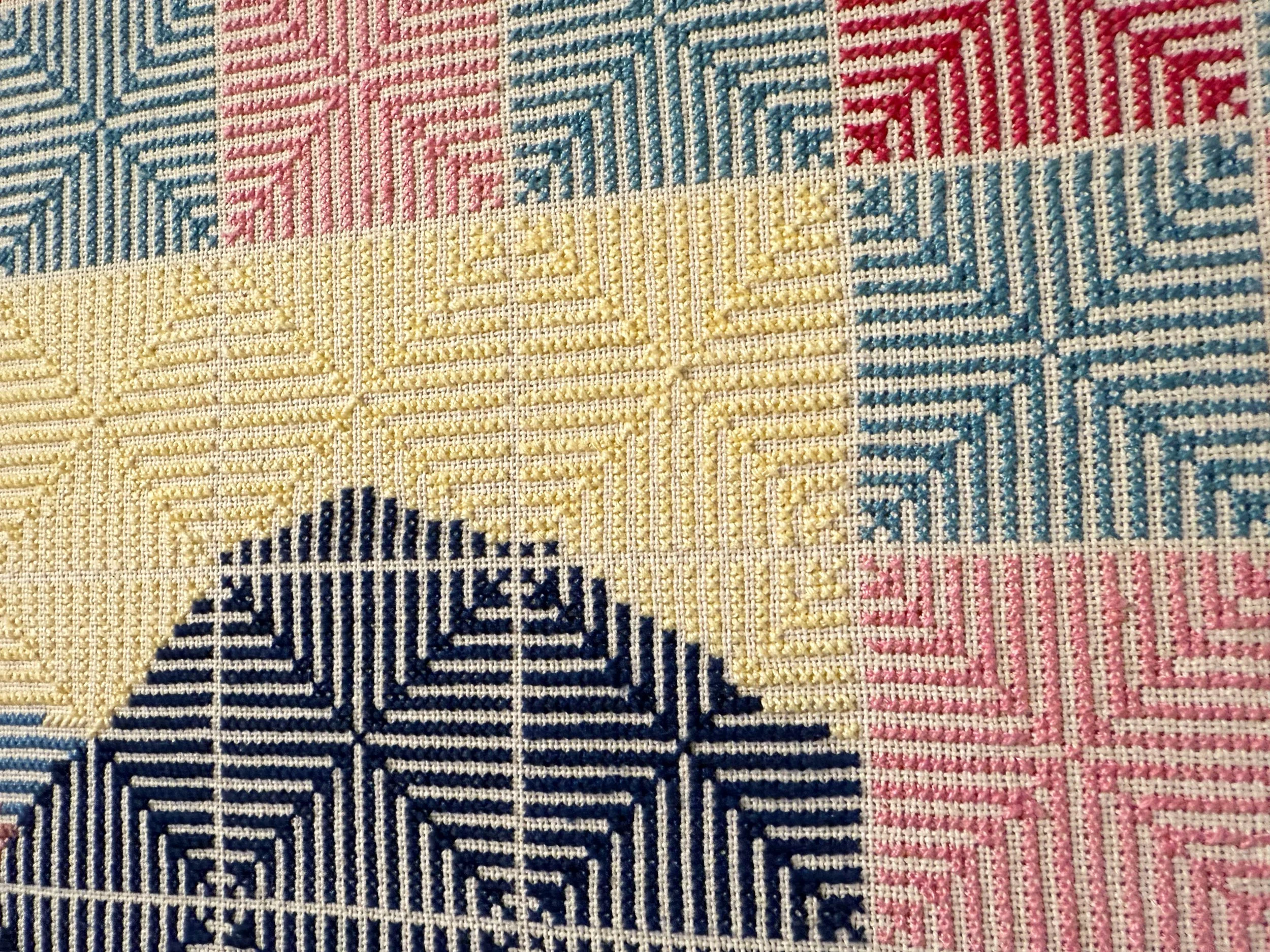

Jordan Nassar has adapted the matrilineally-learned tradition of Palestinian tatreez, or cross stitch—most often found on pillows, clothing, and other domestic arts—to mirror his hybridized upbringing in New York. Each hand-embroidered work is stretched and framed, bringing Nassar’s embroidery practice into a dialogue with painting.

Nassar has created an important body of work in collaboration with craftswomen living and working in Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Hebron, which juxtapose local traditions with a contemporary aesthetic. The craftswomen lay the foundations of his panoramas; beginning with a color palette of their own choosing on areas of the canvas predetermined by the artist, Nassar then embroiders multicolored landscapes within these intricate geometric grids.

At Dawn and in the West, 2022 is a hand-embroidered landscape with shifting red, pink and blue colorways in uniform geometric square patterning. Here, a cascading valley built from the same square stitching, is lit by a yellow sky and cradled between two tan lines of tight pattern. The mountainscape functions as a window in a scrim of squares.

Nassar frequently draws upon the connection between image-making and language. The inspiration for the title of this work stems from poetry written by the Lebanese-American artist and writer, Etel Adnan. (1)The artist says of his imagined landscapes, “they’re conceptually linked to Palestine, a place where land is the crux of the issue, as well as growing up in the Palestinian-American diaspora, so they touch on the dreams of that place and the distance I feel from it. My work is personal and emotional, it comes from both places of joy and of pain…” (2)

Source